Georgia Road is known for some interesting operations, and one in particular is the Georgia Road helper station in Herrin, AL. Located about forty miles from the major terminal at Birmingham, AL, the station of Herrin is home to the “Flat Top Mountain Swingers”. This somewhat unique name is the result of the two notable occurrences that managed to juxtapose themselves squarely in the heart of this vague location. The name was first ascribed by local railroaders and railfans alike due to the manned swing helper station based at Herrin, AL. The Flat Top Mountain Swinger jobs regularly shove trains up and down the winding and heavy graded Flat Top Mountain grade east of Herrin on the Georgia Road Brookwood Subdivision of the Georgia Road subsidiary, the Alabama Interstate RR (ALIS). The name also became synonymous with a group of Bluegrass aficionados who created a band which incidentally hailed from the Alabama sticks around the Herrin location. Folk music circles knew them also as the “Flat Top Mountain Swingers”. T

Ironically, the two reasons that give Herrin a certain local color notoriety are linked. The collection of employees that run the helper locomotives also moonlight as members of the band. Using the Flat Top Mountain Swinger name seemed fitting since members were both railroaders and musicians both linked by the Herrin helper station. Folks poking around the area talk hearing dueling banjos drifting on the breeze around the small office located at Herrin where the swing helper jobs and local maintenance crews base when not out on the main line. Visitors who on happenstance find themselves in the area at the right time and hear the music will find its source around the Herrin Helper Station. Fortunately, it is not a recreation of a cinematic scene from “Deliverance” with a young Burt Reynolds grinning side-mouthed on the small, covered porch facing the railroad. Instead, a lull in trains in the late afternoon or evening finds most of the band members at the office waiting for the next shove. To pass the time, they regularly hone their “pickin’ and grinnin’” craft. The result is ad-hoc mini-concerts of some of the best Bluegrass anthems of all time including original songs based on experience as railroaders in the hills on north central Alabama. Members are as adept at their work as they are at their music, so Georgia Road management even embraces their efforts during employee meetings, family events and publicity events. After all, it is not every day’, that ‘railroading’ and ‘playing’ come together so seamlessly. Locals and visitors regularly park across the road in the old woodyard to take in the sweet sounds coming from the patio at the Herrin office. The lyrics feature ballads with hard work, loss and life on the railroad and in the coal mines. The sets can end as quickly as they start when the ALIS dispatcher queues up the next train to be pushed over the Flat Top Mountain grade. The band takes its music and its job pushing trains equally serious.

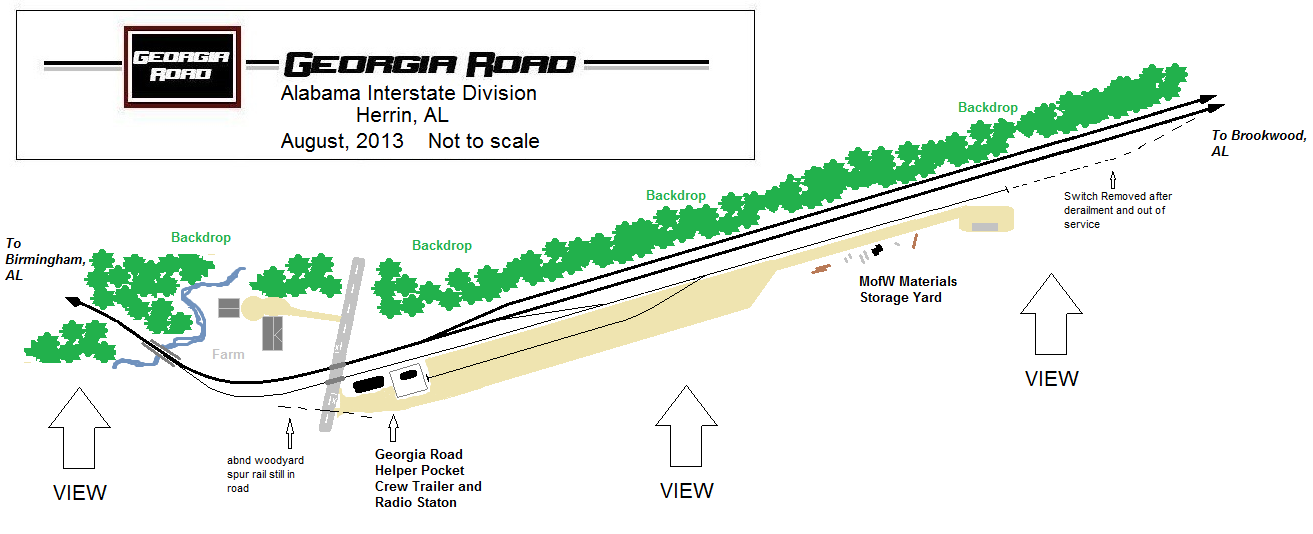

The helper station at Herrin sits at the north end of early 2000s era double track project on the busy Alabama Interstate RR (ALIS) section of Georgia Road Transportation. It is home to the only manned helper station on the Georgia Road. Two sets of helper locomotives swing in and out of the station twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, taking turns pushing as many as 30 trains per day. Herrin sits about halfway between Tuscaloosa, AL and Birmingham, AL at the base of the Flat Top Mountain grade. Any Georgia Road trains moving between major terminals at Memphis, TN and Birmingham, AL have to crawl up or work down ruling grade and tight curvature into the Warrior River Valley. Herrin is a remote place, lost in the black-top gravel roads winding through Jefferson and Tuscaloosa County between Bessemer and Brookwood, AL. It is “smack-dab” in the middle of the Blue Creek Coal seam. The name Flat Top Mountain Grade was the name given way back when the mainline was nothing but an old L&N branch climbing around former Drummond Coal Company strip mine known as Flat Top Mine.

In the formative years of Birmingham, AL, deposits of high carbon coal, Red Mountain iron ore and limestone allowed Henry Debardelaben to establish steel producing mills. Several railroads not only worked the mills, but moves the coal, iron and dolomite from the “Sleeping Giants” mountain chain section of the Appalachian foothills surrounding Birmingham. Birmingham boasted several steel-making mills through the 19th and 20th Century, and one of the busy mining branches worked through Brookwood, AL as part of the L&N Alabama Mineral Belt Subdivision. This line was also a link to the Gulf Mobile and Ohio RR (GM&O) which reached east from Tuscaloosa, AL. What was known then as the Brookwood Branch ran from Bessmer wye in Birmingham through several coal mine locations, including the Flat Top Mine to the hamlet of Brookwood where it connected to the GM&O and more mines. The branch bridged Hurricane Creek and continued through Holt, AL on the river to its terminus on the north side of Tuscaloosa. L&N and the GM&O worked together using reciprocal trackage rights in the late 20th century to maintain interchange, The original station at Herrin AL was established as a steam era helper point at a lonely station named Herrin, AL to move heavy interchange and coal trains over the winding and heavily graded L&N Brookwood branch side of the operation.

By the 1980s, the L&N was part of the Family Lines System and later Seaboard System as Seaboard Coast Line Industries gained control of several key railroads in the area. GM&O was bought by the Illinois Central, who quickly downgraded many of the GM&O links to grow its own. As steel making waned it Birmingham in the 1990s, the Brookwood Branch once again became a clandestine link to the remaining mines around Brookwood, but with most of the remaining coal moving south to the export docks at Mobile, AL. The steam era helpers disappeared during the steam to diesel transition, then reappeared for short stints during coal booms. The branch itself lost favor during the mergers of the 1980s and 1990s, relegated to a back wood interchange with ICG regional spin-off, Gulf and Mississippi Railroad (GMSR) and origination point for Jim Walter and Drummond Coal export coal headed to Mobile, AL. It seemed destined to fall in the history books as “what once was.”

The Brookwood branch would get a second chance in the mid-1990s as Georgia Road worked to piece together a Class One operation with spin-off branch and secondary lines from Norfolk Southern RR and newly formed CSX Transportation. The tired L&N branch became a mainline link to former GM&O lines bought by Georgia Road when KCS decided to divest much of its MidSouth trackage unrelated to the east-west Meridian Speedway. These piece-meal acquisitions gave the growing Georgia Road access to Memphis, TN where it established a western terminal to connect with Western Class One railroads such as UP and BN. This direct link between Birmingham and Memphis changed the Brookwood line from branch to mainline almost overnight. Georgia Road immediately shifted traffic for single line movement and set about upgrading the Brookwood line for overhead Birmingham-Memphis traffic. An extensive rehabilitation project transformed the line with ribbon rail, long passing tracks, and the resurrection of the Herrin helper station to deal with mainline trains running on the heavily graded Flat Top Mountain grade as its curvy steam era right of way be-deviled modern mainline operations. Shoving increasingly heavy trains proved less expensive than runaway cuts of cars generated by constant broken knuckles and drawbars. String line derailments were commonplace when loads and empties were not balanced out of Memphis. With Memphis so far away and unaware of the perils of mountain railroading, trouble with trains moving through Herrin were more the rule than the exception. A manned swing helper station at the age-old base of the grade in Herrin made these harsh realities manageable.

A few short years later in 1999, Georgia Road shocked the railroad world by wrenched the Illinois Central from suitor Canadian National Railroad (CN). Immediately, the age-old Herrin Helper Station and its claustrophobic pre-fab office became the map center of the link between Georgia Road traffic moving from Dallas, Chicago and Kansas City from the west to Deep South destinations like Atlanta, Charleston, Jacksonville, and Miami to the east. The winding line got a complete makeover in the early 2000s with speed signaling, addition of double track over the grade and full remote CTC control. There was even a mainline realignment project and new tunnel to reduce curvature and grading at one of the most troublesome curves near Dolomar. This did not deter the Flat Top Mountain grade from forcing increasingly heavy and long trains to climb and twist. DPU solved many capacity problems, but the Flat Top Mountain grade continued to make operation peculiar at worst and particular at best. Grade and curvature were notorious for breaking coupler knuckles on long and heavy trains. The final 3.5 percent grade between Bessemer and Brookwood remained and the Herrin swing helpers remains also to combat the issue as a permanent fix. To ensure fluidity on what had become the backbone of the Georgia Road, men with steady hands and knowledge of the mountain still needed to help the heavier manifest and unit trains wind in and out of the Birmingham suburb of Bessemer, AL and through the ruling grade of Flat Top Mountain.

So why would any self respecting railfan give such a “middle of nothing” dot on an ALDOT road map a second thought? The answer comes in part from how Georgia Road built its locomotive roster in the first place. Georgia Road found its roots in the spin-off of the former Central of Georgia Railway (CofGA) lines in Georgia and Alabama by Norfolk Southern RR (NS). The move was done by NS in part to provide monies it would eventually use to buy Conrail and relieve itself of the Deep South version of its W&LE sell off a few years before. The transaction created the Central, Alabama & Southern RR (CA&S). The CA&S lived a remarkable but short life, falling into bankruptcy and court appointed sale. Georgia Road would step up and buy the CA&S estate with ideas of reforming it into a profitable railroad. What NS could not predict was how the Georgia Road would reach beyond what was the branch line remains of the CofGA system. Somehow Georgia Road gained traffic and with lucrative coal and intermodal contracts (the APL contract being the first and greatest), found ways to expand in ways the NS lawyers working to bind it could never imagine, Georgia Road spread into Florida and the Carolinas, funneling traffic between Memphis and Birmingham gateways to link the Deep South and the rest of the U.S. A decade later in 2008 found the railroad rated at Class One status as a welter-weight railroad known for its innovative and customer focused approach that grew traffic rapidly.

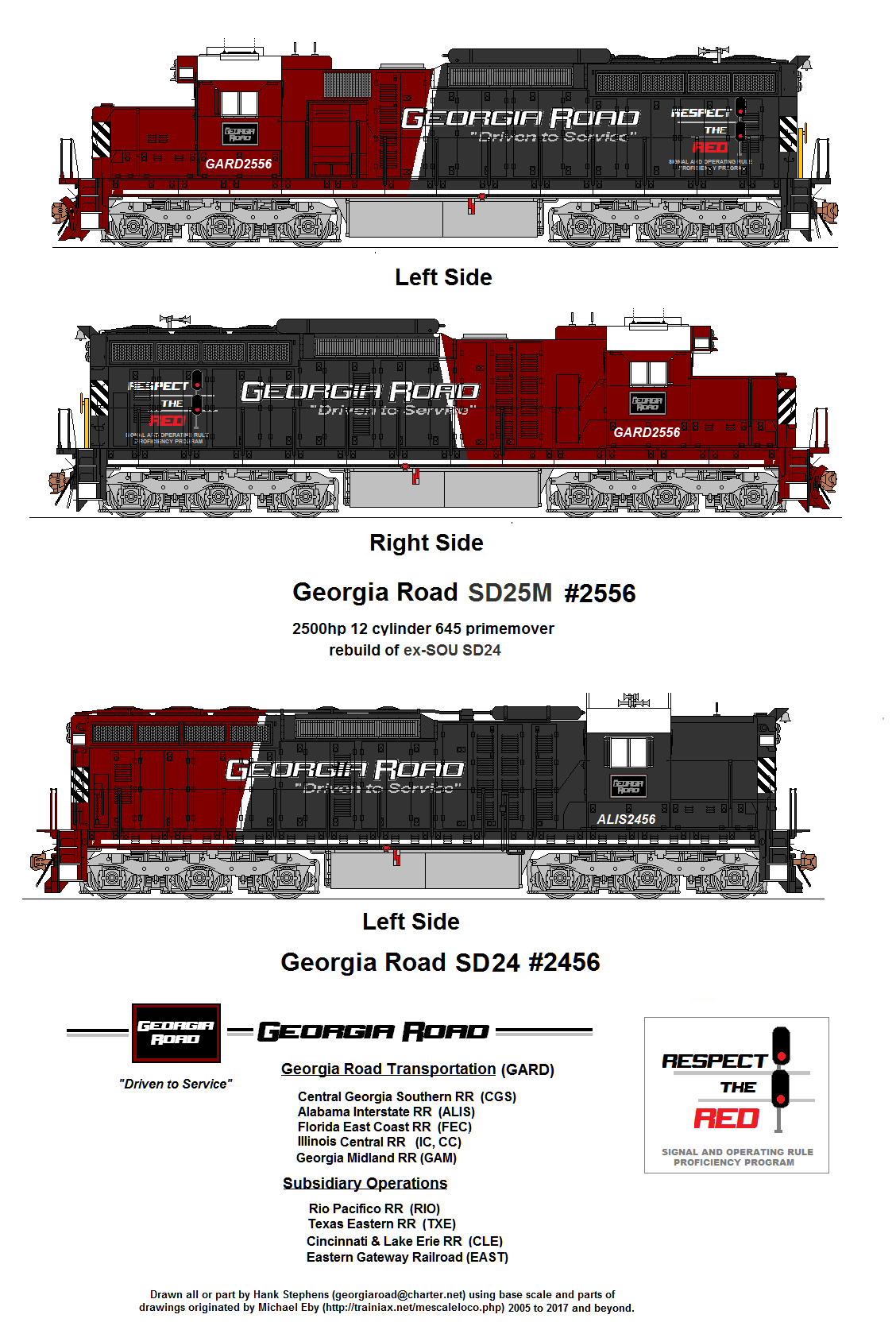

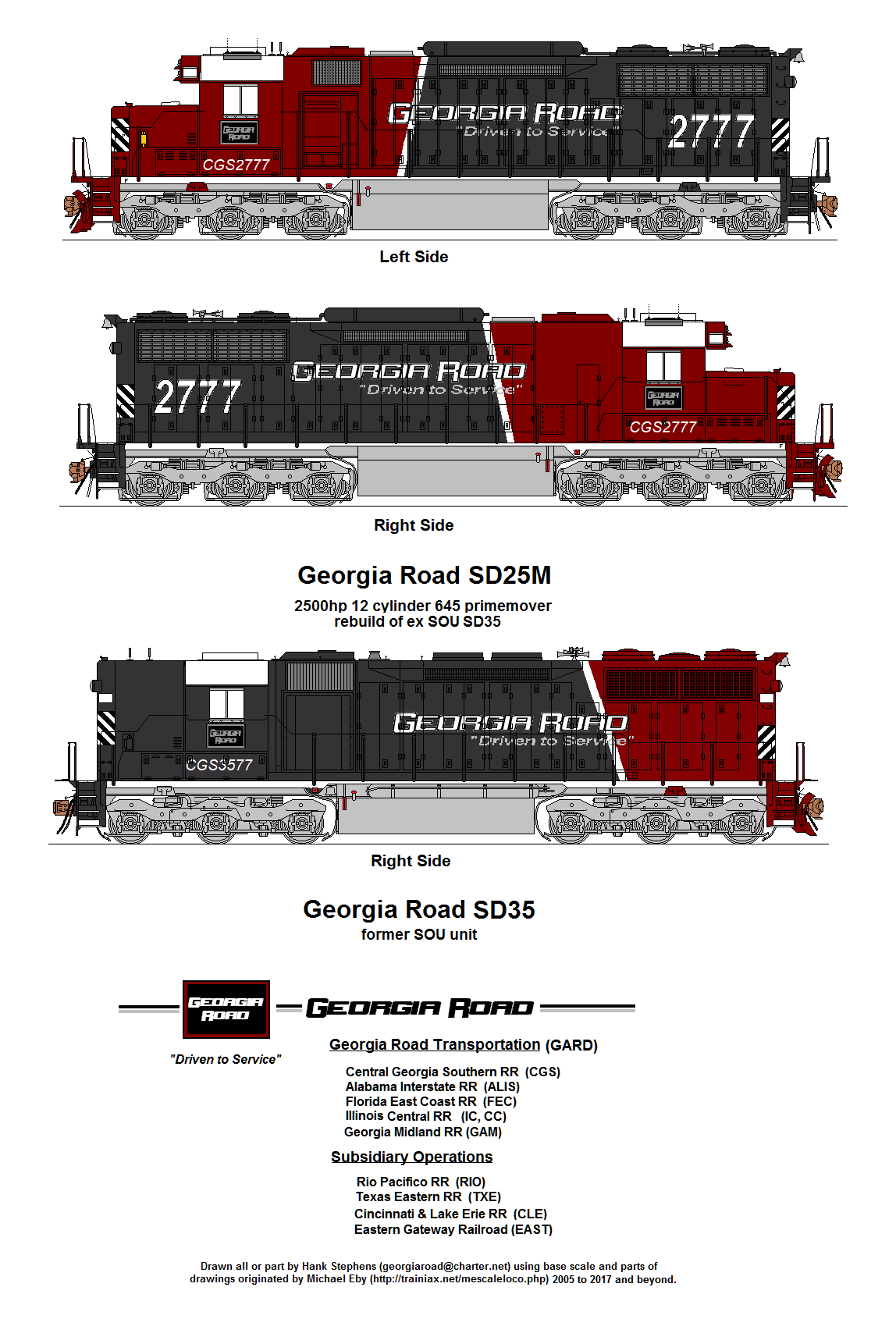

The locomotives that made the Herrin based Flat Top Mountain Swingers” remarkable were rooted in the history of how Georgia Road came about. Georgia Road inherited old Southern power which carried over from the defunct CA&S it purchased and reorganized in 1996. As a result, it had more than its share of ex SOU SD24, SD35 and SD45 units, most with as delivered SOU style high short hood operation. Many were worn out, but in the halls of contract rebuilder Stephens Railcar, many found new life following overhaul and rebuilding. The chronically power short Georgia Road always seemed to need even the oldest and most worn cores to feed a variety of capital and life-extension projects used to economically fill holes in the combined system locomotive roster. Those units that seemed to soldier on despite the years, and usually settled into transfer and helper service around Birmingham, AL. This was close to Stephens Railcar and the Georgia Road back shop in Irondale, AL where any ailments could be quickly seen after and availability maintained. It never hurt that the Road Foreman of Locomotives at the Birmingham Terminal was a former Southern man, and he carried a sweet spot for the very same locomotives he ran as a Southern Railway boomer in the 1960s and 1970s. It was no wonder either that many of these units ran in similar stance as they did in their factory fresh days on the SOU, with the only difference being these units sported new burgundy and black Georgia Road paint. Most still ran long hood forward as “the Almighty and Southern CEO of the Southern Railway Bill Brosnan intended.”

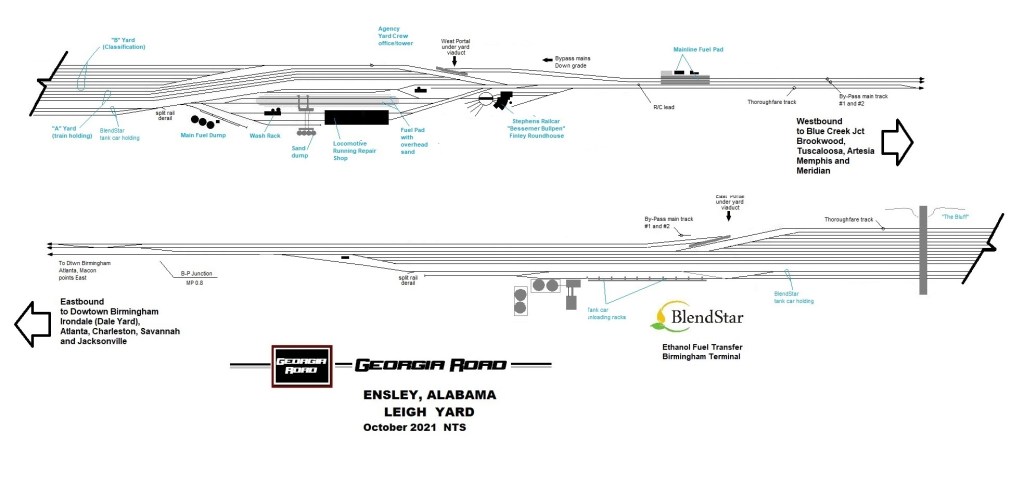

By the 2020s, the numbers and days of non-rebuilt old Southern locomotives are only a handful. While still lovingly maintained by the personnel at the Georgia Road Leigh Yard Service Shop where they are assigned, modern locomotion is slowly winning out. (Understand that the word “lovingly” is not used lightly since locomotive maintenance personnel “better love ’em if they intend to keep a job” with that old SOU Road Foreman as the boss of both the original Irondale back shop and the newer Leigh Yard Service Shop.). He is known for regularly marching up and down the hostler lines and service pits hollering “give ’em one day more, or hit the door!” These fifty-year-old units are now finding themselves outclassed by Stephens Railcar Revolution Series Rebuilds that meet the newer EPA emissions and FRA collision standards, or flat out replaced by the newest “techno-toaster” from EMD or GE. If asked about this, the old Foreman is quick to cut his eyes and sneer that his grandson will be shaving with the metal in these new units long before they get even close to the service life of his old SD24 and SD35 units. He is also quick to remind anyone that “his units” are pushing those “damnable electronic nightmares” up the Flat Top grade, not the other way around. One does not have to listen long to understand he has a point. “Tired or not, these first generation EMD beasties are simple, rugged and just never quit.”

Georgia Road decided that the whole class of SD9, SD24 and SD35 locomotives needed rebuilding or replacement by the early 2000s. The TGX Program Revolution Series SD44R-CAT rebuild was originally earmarked as a replacement for many of these units, but with the assimilation of the DME-IC into the core system demanded that the remanufactured units fill gaps in the growing roster rather than as replacements for existing units. While these new Revolution units frequented the locomotive pools around Birmingham, they almost always ran for a break-in period before leaving for other assignments. The helper crews always laugh when asked about them, indicating that they are the designated “cowboys charged with breaking the rebuilds so they can go to work reliably for someone else on the system.” The new units would hang around for a period, then pack up and leave for permanent assignment pools elsewhere. The old SOU engines quickly filtered back and resumed exactly where they were left off. After it became apparent the old SOU first-gen units would not be replaced, the decision was made to use the old SD9, SD24 and SD35 units as cores for the SD25M Program to extend their lives indefinitely. Since Georgia Road figured it could not do without the old horses, it looked to rebuilding them much as it did with the old GP38, GP35 and GP30 units in the GP25M program. The GP25M units were completely remanufactured by Stephens Railcar and found themselves proven platforms in crack intermodal service fresh out of the shop. The six-axle version of the program followed suit, also building the unit around the turbocharged 16 cylinder 645 primemover. The remanufactured units could match a moderately ballasted SD38 with half the emissions and wheel slip potential. The SD24 and SD35 cores were interchangeable in the program and in the same number block on the Georgia Road roster. In order to match fuel capacity, the tanks had to be reworked on the SD24 and SD35 similar to the GP25M version. Everything was standardized in the remanufacturing process as much as practicable. While not externally all equal, key parts were fully integrated across core locomotives for reduction of spare parts inventories and interchangeability internally. These SD25M units began replacing the old first-generation SOU units on a one for one basis. Second hand SD38 units were acquired to fill gaps as the core locomotives were pulled for rebuilding, adding yet another similar model to the transfer and switching power pool at Birmingham. As a result, sets of SD25M, SD38 and the remaining old SOU units could regularly be found humming along with sets of Bluegrass favorites emanating from the station at Herrin.

As of this writing, the original as built units number under two dozen. Only one SD9 is left, chop-nosed and rebuild years ago after a grade crossing collision (likely why it continues in its current state). The SD24s are down to six, and the SD35 units are four. The old SOU Locomotive Foreman is near retirement, but he continues to keep the iconoclastic locomotives in good working order. He has made peace with the idea that the SD25M rebuilds are close enough versus the real potential of a complete extinction of the old SD9, SD24 and SD35 models if Georgia Road decided to set the remainder aside. No new SD25M rebuilds have debuted since the 2020 Pandemic that idled so many programs, Georgia Road seems to have moved on, working with Stephens Railcar on the new TGX Program ENCORE initiative which includes alternative fuel experiments. For now, they work daily on borrowed time, mostly in yard or helper service. As they rotate out for servicing and newer models substitute in, one never knows if this will be the last time. At least for now, the Bluegrass tunes still float on the wind around Herrin, AL as throaty first generation EMDS keep time humming in the background. When not sitting at the far-flung station, their distinctive growl echos around the Flat Top Mountain grade as they shove another train up Flat Top Mountain. These experiences would make for a good Bluegrass song. There is a good chance a visiting railfan will hear it if in the right place at the right time!